Hidden Temperature Sensor

Last Updated : July 22, 2017

Well, it’s not exactly a clickbait. Because there is indeed an internal temperature sensor in ATmega328(P). But I can’t say it’s hidden because it’s mentioned in the datasheet.

How I Played Sherlock

While reading the ATmega328 datasheet for preparing a concise register-reference, I came across the ADMUX register, which listed a temperature sensor’s analog channel included in the MUX[3:0] bit-description table.

Wait what? Inbuilt Temperature Sensing?

Ctrl+F took me to Page 316, titled Temperature Measurement, which had the following information written in abstruse technical words:

- The temperature measurement is based on an on-chip temperature sensor that is coupled to a single ended temperature sensor channel.

- The sensor is activated by writing ADMUX[3:0] as 1000.

- The internal 1.1V voltage reference must also be selected for the ADC voltage reference source to give better results.

Furthermore, the sensor’s output voltage finds an approximate linear relation with the temperature:

| Temperature | -45°C | +25°C | +85°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage | 242mV | 314mV | 380mV |

Typical Cases

Try It!

No external connections are required, the Arduino board is enough.

#include <avr/io.h>

void readTemp()

{

//setup Analog Channel Input to

//Internal Temperature Sensor

ADMUX |= _BV(MUX3);

//give some time to set it up.

delay(5);

//Start Conversion

ADCSRA |= _BV(ADSC);

while (bit_is_set(ADCSRA,ADSC));

//read analog data from both registers

uint8_t low = ADCL;

uint8_t high = ADCH;

//merge data

int reading = ((high << 8) | low);

//calculate corresponding temperature

float result = (((reading) - 314)*0.942 + 25);

Serial.print(reading);

Serial.print("\t");

Serial.println(result);

}

void setup()

{

//setup internal 1.1V reference

ADMUX = _BV(REFS1) | _BV(REFS0);

Serial.begin(115200);

}

void loop()

{

//calling analogRead somwhere else in the code

//can possibly disturb our configuration

//of ADC settings.

readTemp();

delay(1000);

}

Testing

The results from the LM35 look so promising because they are precision integrated-circuit temperature devices with an output voltage linearly proportional to the Centigrade temperature. It is pre-programmed to output only \(T\pm 0.5\) oC.

The output voltage for the ATmega’s temperature sensor generally varies from one chip to another.

What’s also important is to notice that the output is measured against the internal 1.1V reference, which changes terribly, given it’s a reference.

Without calibration, I received horrendous results like these:

| Actual TemperaturePrecision Thermometer | LM35 Output | Inbuilt Temp Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| 30.0 | 30.5 | 53.26 |

| 25.0 | 25.0 | 47.60 |

| 20.0 | 19.5 | 42.89 |

| 15.0 | 16.0 | 40.07 |

| 10.0 | 10.0 | 35.36 |

All measurements in degrees Centigrade

To take readings, I assumed a linear plot which gave this equation

where \(y\) is analog reading in mV and \(x\) is oC.

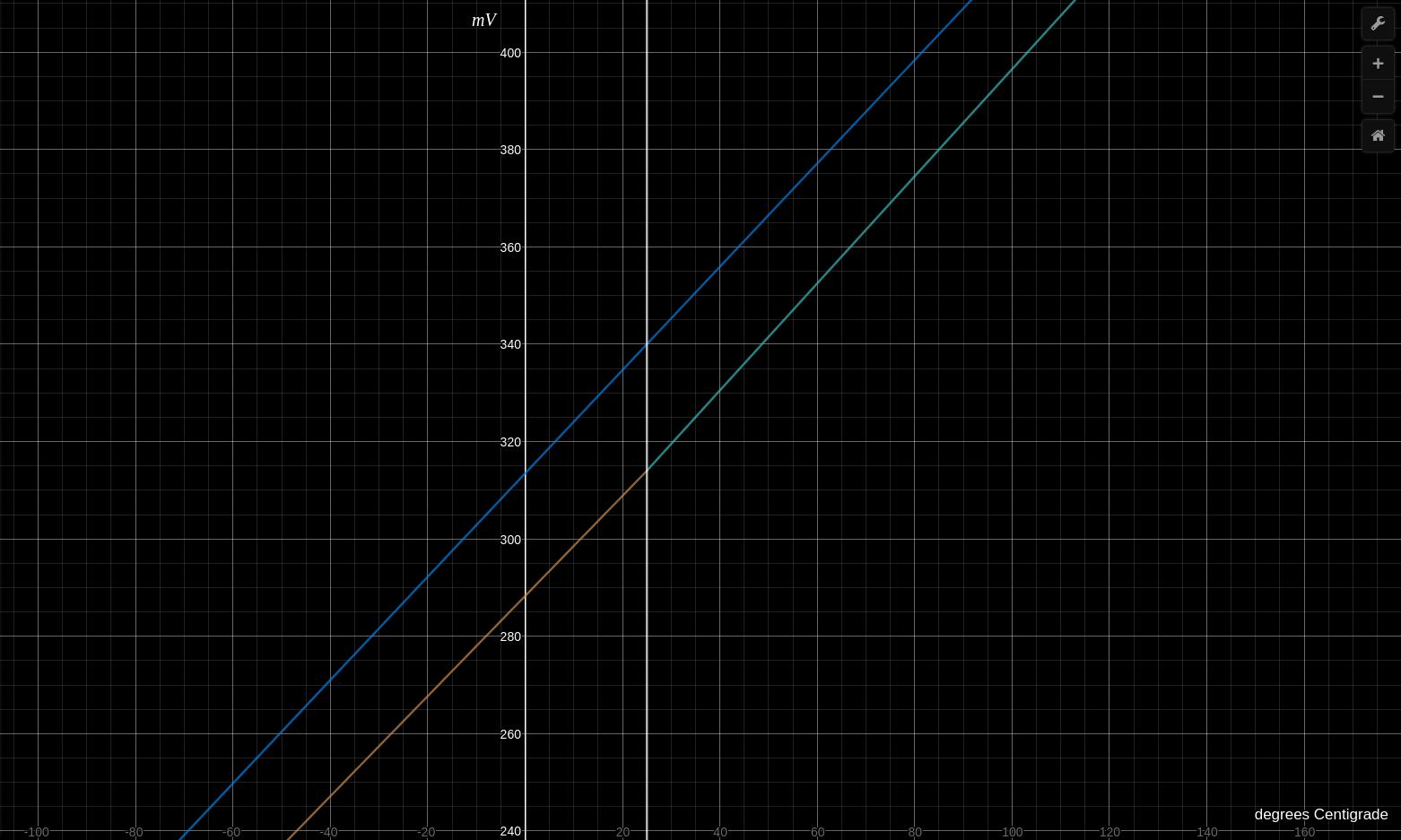

The above graph shows typical values in green and orange (well okay, turquoise and sienna), and measured-values in blue.

The white line is x = 25oC.

Note that I’ve assumed a direct linear interpolation between the minimum and maximum values for my readings (blue), which gives an effective slope of 1.0615 (or \(\frac{138}{130}\)).

Yes, I sat in an air-conditioned room to allow the temperature to drop from 30oC to 20oC, and then put everything in a refrigerator to get to 10oC.

And I wonder where my free time goes.

Let’s not consider readings below 20oC, because I feel that the encapsulating epoxy layer of the ATmega chip would have acted as an insulator for the temperature sensor inside, thereby creating a decent temperature gradient. And the time for which the ATmega was in the refrigerator wouldn’t have been enough to bring down the chip’s temperature.

But that does not explain the effing 23oC gap at room temperature, does it?

I was pretty sure that the reference I was using (the inbuilt 1.1V voltage reference) wasn’t actually giving out 1.1V.

Blind shot, but worth it.

The AREF pin outputs the current voltage reference being used. Measuring it resulted in, well, 1.02 V.

Doing some reverse math, it can be seen that

which is the reading that I would have received from the analog reading.

Adjusting this reading for a reference of 1.02V gives

and 319 when put in the original equation gives 29.69, uncannily close to 30.

| Actual TemperaturePrecision Thermometer | LM35 Output | Inbuilt Temp Sensor | Adjusted Readings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30.0 | 30.5 | 53.26 | 29.69 |

| 25.0 | 25.0 | 47.61 | 24.99 |

| 20.0 | 19.5 | 42.89 | 20.29 |

| 15.0 | 16.0 | 40.07 | 17.46 |

| 10.0 | 10.0 | 35.36 | 13.10 |

All measurements in degrees Centigrade

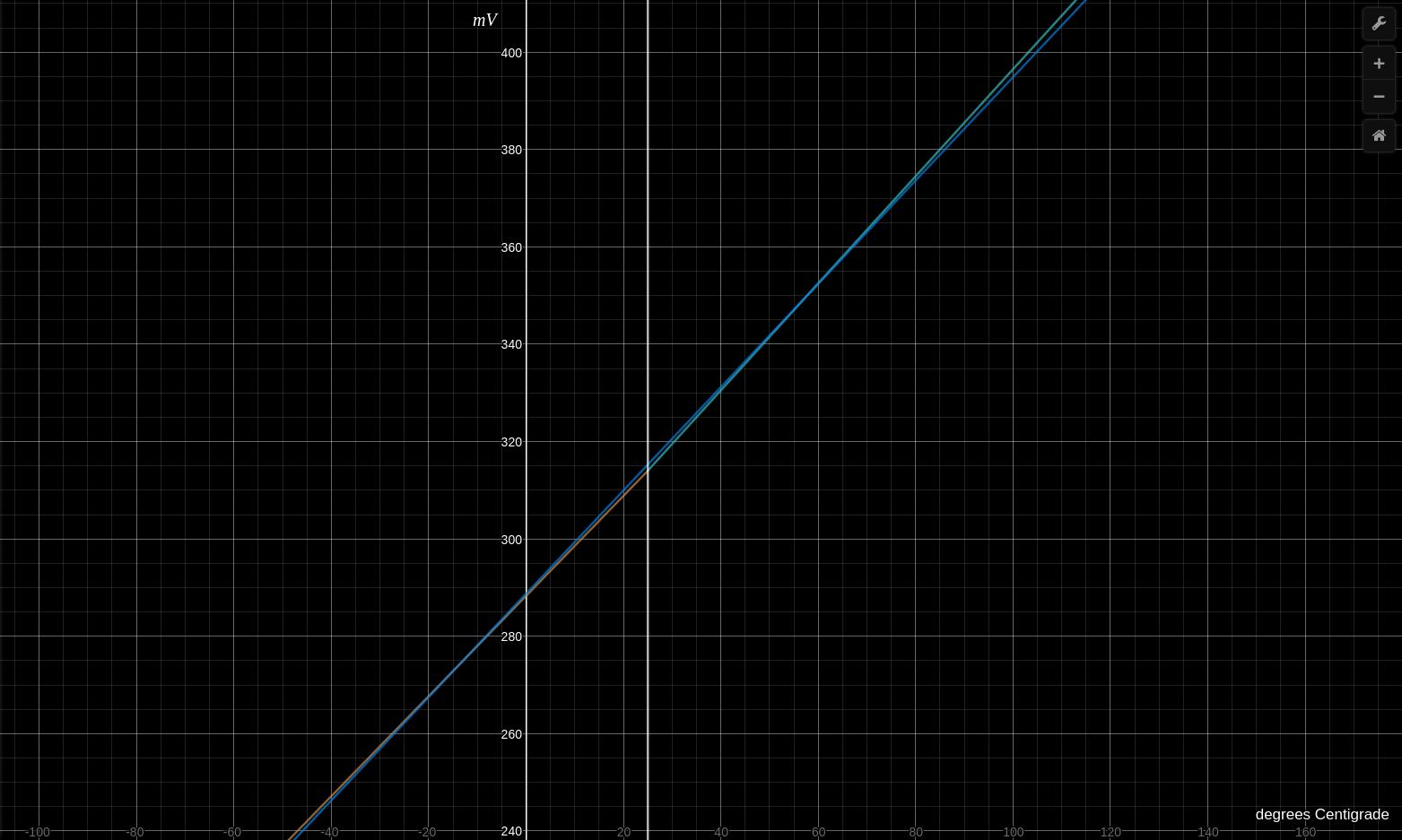

The new correction gave a plot that snapped right onto the given typical graph. Well, almost.

The complete graph can be viewed here.

Calibration Specifics

I have a feeling that I haven’t been able to clearly explain my calibration procedure. The following formula neatly compiles everything.

or, in proper English,

To calculate the the VREF Correction Factor,

- The Error-Offset is just present to fine tune the calibration and varies for individual practicals.

- It is recommended to use the EEPROM to store the values of variables.

- The process is a one-time calibration if the supply voltage doesn’t change much.

- Please note that the above formulas are applicable for any voltage-reference used.

I feel it’s quite a previlege for millenials to witness such grand tech while using elementary mathematics and basic computers. I mean, it doesn’t really require actually knowing about thermocouples to use the temperature sensor. It’s just there, and anyone with enough brains to read the datasheet can use it easily. It’s obvious that all this grand tech is not the brainchild of just one person, but a collective effort of thousands of people. What is also obvious is that we have reached a stage where a human cannot be expected to store all the open-source data in the world.

Therefore, as true millenials, it is nothing but our ethical duty to choose specific areas that interest us, so that we can collectively contribute and make things worth being proud of.

Otherwise millenials will be easily tagged as comparitively the most educated people with the lowest contributions in all of human history.