Micron Technology, Imagination Technologies, and HiAccel Lab

Hmm… The world ended in March 2020. We are all ghosts today. Or, well, were at least supposed to be, instead of the loves ones that became ghosts.

4 years later, so much has changed.

Take Jekyll, for example. I make this post after 3 hours of peeling my eyes and pulling my hair while scrolling through StackOverflow. It took me about forty trials to set up rbenv and Jekyll correctly, just to add this post.

Frankly, I don’t even know if the current setup is how it should be installed. All I know is that it works.

Every new configuration line I add feels like removing a block from a Jenga tower. No matter how carefully I deal with this setup, it is bound to collapse in the future.

Micron

I spent the later part of 2020 and 2021 learning about Universal Flash Storage (UFS) at Micron, and owning the transport and application-level host interface verification. This was a fantastic team I worked in. There’s some faff about LinkedIn on how smooth the onboarding process is and how excited everyone is to join a company. But it is now my iron-clad understanding that the quality of your mentor is what defines your career trajectory too. I was lucky to have a great mentor, who didn’t think of me as a mere side quest even when I joined Micron at a fast-paced time when they were moving to a new internal architecture. The learning curve at Micron was steep. But what better challenge can you throw at a college graduate sitting home with a brand-new, fully-reimbursed workstation? A new architecture meant making new files with my name in the author’s title. It was quite validating to be making such a change to the codebase during my first year at a MNC like Micron that was already celebrating 42 years of establishment when I joined. By the end of two years at Micron, I owned the host-interface to our first UFS 4.0 controller. I wrote firmware, debugged waveforms, debugged datapath software on FPGA emulations, debugged link errors during post-silicon validation, and eventually got to a stage where I had enough understanding about the architecture to write high-performance firmware.

What I cherished most though, was talking to engineers from multiple geographies and finding that everyone is as confused as the other. But engineers have this flex, that they hammer something here and wrench something there and find precisely and exactly what is wrong. The redemption of information and knowledge in that moment is nothing short of an adrenaline rush.

There are 3 key moments during my verification experience that I will never forget.

- The most bugs I have found as a verification engineer were obviously in my own code. I remember facing a complex issue related to a datapath hang (which can occur due to any of its constituent IPs failing) that was found out to be a RTL issue. Pointers are quite common in high performance firmware (and they do nothing more than organise memory addressing). However, one flaw in a multi-level organisation of memory addresses can have effects that can easily push a developer to insanity. What I finally realised, after about two days of debugging (and I quote from my journal) was:

“There’s a pointer (P) to a pointer to a structure of pointers to lists of pointers to decoder-buffers (D). Pointer P receives an invalid value due to wrong arithmetic and makes the datapath hang because the decoder tries to access something not available on its memory bus. Ooof!”

- The second moment was when the engineering sample had been brought in at the San Jose site, and the team there had setup remote connections for us to work on through the night. We were a really hardworking bunch who wanted to achieve something called a Day0 lead. The first time the chip is powered, there are all sorts of voltage and current measurements are taken. The internal ROM is configured to put some boot messages and if successful, a greeting on UART. The funny thing is that UART works on a local clock, and so the first few reads are all garbled. Because of the manufacturing process of the silicon wafer, each chip is unique and produces a different clock than what is expected. For example, a chip configured to produce 25MHz internally might not necessarily produce the exact value, leading to all sorts of unexpected behaviour. The design compensates for this by providing a trim register, which controls the voltage being fed to the internal PLL, which in turn acts like a digital knob on the internal clock frequency. Multiple reloads of the firmware performs a linear sweep or binary search for the perfect trim value of the internal oscillator to match the expectation. Until this value is matched, everyone sits on call with their brows sweating profusely at the terminal screen sharing the UART output. There is absolutely no way of knowing if the chip will work. Because hey, garbled output can be anything - it can be an error too. We’ll never know unless we understand what the little silicon guy on life-support test-bed is saying. While I was evaluating the gravity of verification as a job, the terminal flushed with boot messages revealing all sort of internal chip stats, ending with a nice

HELLO FROM ******** ROMAlthough I can’t share the name of the project due to CIPA considerations, I can share the hit of adrenaline I felt when a tight lump in my throat melted into my heart, making it resume beating more aggressively than it had ever before. I was floating. It was as if 4 years of my undergraduate education in Electronics was suddenly redeemed, that I deserved to be part of this success, albeit standing on the shoulders of giants. The applause on the call doesn’t matter. Corporate beer doesn’t matter. You know you’ve made it. You’ve done your part. And you’re proud of it. That’s a distinct feeling of decimating any lingering vestiges of impostor syndrome. I will always remember my time working with the SoCC-DV team at Micron, Hyderabad for this very reason.

- Working with post-silicon validation was humbling, to say the least. The bursts that would take 30 hours to simulate on compute-farms would take 20 ms to finish in the real world. We were seeing an error in one of our end-to-end tests, where the device was performing fine and transfer TiBs of data in low-performance modes, but would fail towards the trailing end of 2MiB when using its full bandwidth. This was weird. We rinsed through the firmware looking for modules going out of coordination after transferring ~2MiB of data. Next, we re-simulated everything in RTL and discussed whether some RTL behaviour was missed to be checked. Further, different sort of expensive gadgets and scopes were brought in to log these real world transfers at 40Gbps. And I kid you not, we checked everything from the firmware binary and handshake signals to the voltage measurements on the copper wires. Everything couldn’t have been better. So, what was wrong. An engineer, who was responsible for the hardware setups, said he was going to redo the entire setup. His request was dismissed twice, under the claim that doing so would increase the work and introduce unknown errors instead of solving the obvious ones right now. The third time, he was allowed to do it. I was there. What we found while intending to clean the coaxial copper cables that connected the RX-TX lanes between the host and the device, left us looking at each other almost on the simultaneous verge of tears and laughter. For some reason, I remember that moment with the memory of the tone that used to play when Mario would lose a life.

The coaxial cable had a pin at the centre, and a tubular shielding on the side. A small section, hardly 20 degrees out of the 360, had chipped off and was hanging loose. The touch of a finger dropped this gold plated flake on the white table. It was this flake that was the reason that low-speed transfers worked flawlessly, but high-speed (high frequency) transfers saw all sorts of weird capacitance effects making the transfer fail roughly around the time when 2MiBs had been transferred. 1/12th of a tubular connector failing, overruled all the fault tolerance we had designed in all layers of the stack - from the link level to the application firmware. There’s a saying in the semiconductor industry, I understood it in that moment.“Semiconductor Engineering industry is not rocket science. It’s more complex”

Imagination

Saying goodbye to Micron was a tough decision. I was restarting my career as a design engineer, essentially discarding the headstart and promotions I would have enjoyed had I stayed in verification. Imagination Technologies had already worked on an in-order CPU core, that they were trying to expand into a ASIL-D certified processor. The weight of responsibility is crazy. You certainly don’t want the processor to delay triggering the Collision Avoidance System (CAS) because it was busy blinking the lights for the lane-assist.

Linting and CDC is mostly what was on my plate, and I kept feeling that there was so much more I wanted to explore. Linting would never give me that experience, and a choked hierarchy would never offer me anything other than linting (atleast in the then-foreseeable future).

HiAccel

HiAccel works on a breadth of topics related to computer engineering - HPC accelerators, novel architectures, and compiler support for the same. I am glad to be working with brilliant, clever colleagues who share my interests and frustrations.\

I moved to Vancouver in Fall 2023, and what a pretty place this is!

The air is cleaning out my lungs as quickly as the expenses are clearing out my wallet. It is fun to return to student life. But let me not romanticise it for you. In another universe, I probably wouldn’t have liked the change in lifestyle. This type of a lifestyle change is quite subjective and is only for the brave at heart.

I prefer to believe I am ദ്ദി ༎ຶ‿༎ຶ )

hehe.

I often wonder where I will fit better - academia or corporate.

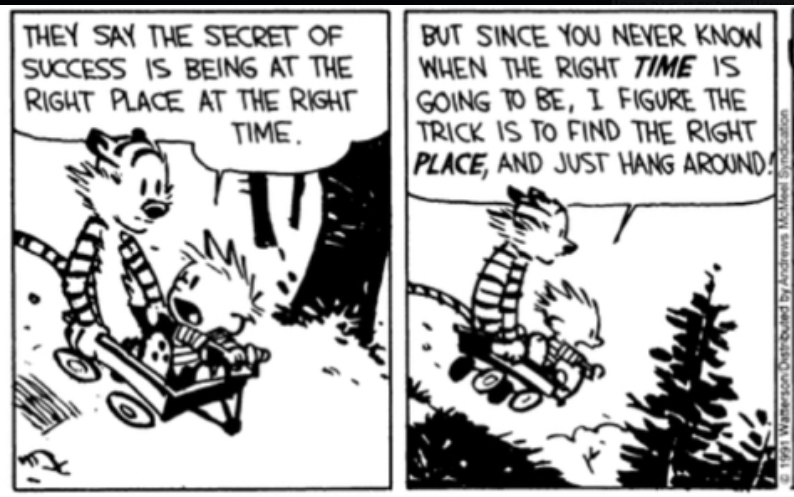

I don’t know, honestly. All I know is that I am trying to follow Calvin’s advice.

What else can I expect myself to do, anyway?